You don’t mind sleeping among the coffins, I suppose? But it doesn’t much matter whether you do or don’t, for you can’t sleep anywhere else.

–One of the kindlier statements addressed to Oliver Twist at the beginning of the novel

I like to think of Charles Dickens as the Joss Whedon of his day—a popular storyteller who churned out episodic adventure after episodic adventure, keeping viewers—er, that is, readers—hooked with cliffhanger after cliffhanger, rarely allowing his love interests to have more than a moment’s true happiness, and constantly killing off beloved characters just to twist all of the knives in the hearts of his fans a little bit deeper.

Oliver Twist, his second novel, epitomizes every aspect of this.

By the time Dickens began to write Oliver Twist at age 24, he had published his first book, Sketches from Boz, to mild success, and had just finished up the serialized The Pickwick Papers, which had gathered more and more readers as installments continued to appear. The success of The Pickwick Papers allowed him to sell Oliver Twist to Bentley’s Miscellany.

As with The Pickwick Papers, Oliver Twist appeared two or three chapters at a time until the very end, when Dickens’ editors apparently decided that a lengthy (and, to be honest, somewhat tedious) chapter wrapping up various plot threads deserved its own separate publication, as did a considerably more thrilling chapter focused on the final confrontation with a murderer. Bentley’s published one installment per month during 1837-1839, just enough time to allow excited readers to talk and drum up interest (in the 19th century version of Twitter). Dickens then authorized a 1838 book (the 19th century version of DVDs) that let those readers willing to shell out extra money get an early look at the ending (the 19th century versions of pre-screenings and HBO).

(Ok, I’ll stop with the metaphor now.)

Probably the best known part of the book is the first half, which focuses on poor little orphaned Oliver Twist and all of the terrible things that happen to him as he’s shuffled off from the poor cold arms of his dead mother to a horrible branch-workhouse/foster home, to an even worse workhouse—scene of the pathetic “Please, sir, I want some more,” scene, to various hellish job training programs, to a terrible home with an undertaker, to a den of young thieves in London, run by the sinister Fagin, where Oliver is briefly forced to become a thief.

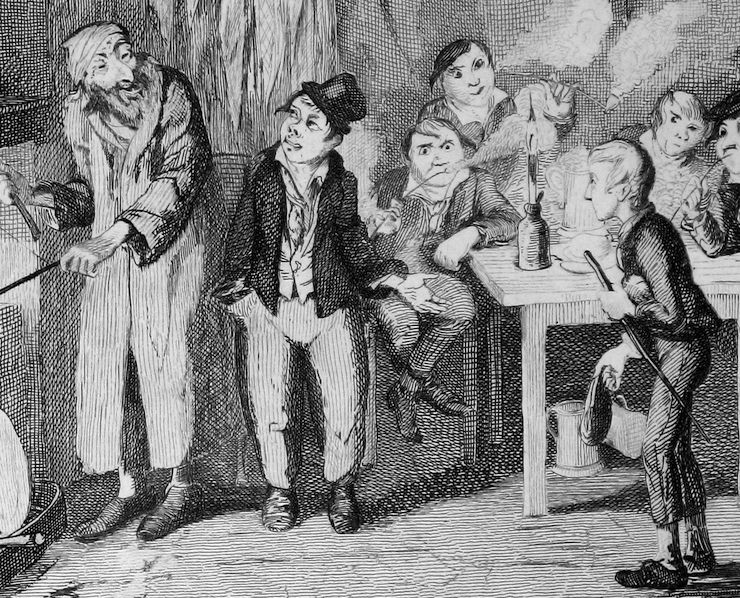

With his creepy habit of saying “My dear” to absolutely everyone, including those he clearly does not have kind thoughts about whatsoever, Fagin is one of Dickens’ most memorable characters, and also one of his most controversial. Fagin is continually described in demonic terms—to the point where, just like a vampire, he seems to have a horror of sunlight and even regular light. That’s not exactly unusual for the villain of a novel, especially a deeply melodramatic Victorian novel like this one, but what is unusual is that the original edition of Oliver Twist (the one currently up on Gutenberg) continually refers to Fagin as “The Jew” or “That Jew”—more often, indeed, than the text uses his name. This, combined with Fagin’s greed and miserly behavior, has led many critics to call Oliver Twist anti-Semitic. These critics included acquaintances of Dickens who reportedly objected to the characterization and the language used to describe Fagin. The second half of the book (written after the reactions to the first half of the book) uses the phrase “The Jew” a little less, and subsequent editions edited out several instances from the novel’s first half, but the charges of anti-Semitism remained, even when Dickens created positive portrayals of Jewish characters in his later novel, Our Mutual Friend.

I can’t really argue with any of this. But interestingly enough, Fagin is not, as it happens, the worst person in the novel. That honor goes either to Monks (who is so over the top evil that I just can’t take him seriously) bent on ruining little Oliver’s life and destroying some perfectly innocent trapdoors, or Bill Sikes (who is at least realistically evil) the one character in the book who commits actual murder. And in many ways, Fagin is also not quite as bad as the various officials and foster parents in the beginning of the novel who are deliberately keeping children half-starved to line their own pockets with extra cash, or at least indulge in a few luxuries for themselves, while sanctimoniously lecturing others on responsibility and charity, or the chimney sweep who has been accused of “bruising” three or four children to death already and is looking for another one.

Fagin is, after all, the first person in the novel to feed Oliver a decent meal. He’s also, to give him full credit, one of only two characters in the novel to recognize that a woman is getting physically abused by her partner, and to offer her practical assistance. Granted, he has his own motives for offering this assistance, and he later betrays her to her partner, an act that leads directly to her death. Still, Fagin is one of only two characters to at least offer help, something that puts him in a rare category with the angelic Rose Maylie, the heroine of the second half of the book. Sure, he’s training kids to be thieves and often beats them up, he lies to pretty much everyone, he plots to get rid of his partners, and he pushes poor little Oliver through a hole and later tries to kidnap and kill the poor kid, but, er, he could be worse. He could be another character in this novel.

Anyway. This first, much more interesting half of the book ends with little Oliver finally landing in the kindly hands of the Maylie family—the angelic Rose and her benevolent aunt Mrs. Maylie—where he could have enjoyed a quiet, happy life had not readers responded so positively to the entire story, demanding more. Dickens acceded, continuing on with an even more melodramatic second half that included evil half brothers, doomed lovers, self-sacrificing prostitutes who don’t take a perfectly good opportunity to get out of a situation they hate like WHY DICKENS WHY, dramatic captures, a murder, and quite a few coincidences that are, to put it mildly, a bit improbable.

If you haven’t read the second half, by the way, this is your fair warning: to quote the text of The Princess Bride, some of the wrong people die. If you really want to understand Dickens, all you need to do is read the last couple of chapters where, right in the middle of what looks like a nice happy ending, Dickens randomly kills someone off, sending poor little Oliver into floods of tears again, like THANKS DICKENS.

It’s not the random deaths that mar the second half, however—especially since at least one of those deaths can’t exactly be considered random. Or the fates dealt out to various characters which, with the exception of that certainly random death, seem generally fair enough, but rather, the way Dickens abandons the satire and social realism of the first half of the novel for an overly tangled, melodramatic plot and an (even for the 19th century) overwrought and clichéd romance, topped by a scene where the lovely Rose refuses to marry the man she loves because she’s not good enough for him, which might mean more if Henry was good enough for or, more importantly, either of them were particularly interesting people. Since neither character appears in the first half, I can only assume that this romance was added by editorial or reader demand, especially since it never amounts to much more than a sideline.

Having added that romance in the second half, however, Dickens seems to have balked at the idea of adding further characters, thus creating contrived circumstance after contrived circumstance, as when, for instance, minor characters Noah Claypole and Charlotte from the book’s first half just happen to end up working with Fagin’s gang in the second half. It’s not that it’s particularly surprising to see Noah Claypole end up as a thief—that did seem to be his destined career. But as Dickens keeps telling us, London is big, and it seems more than questionable that both Oliver and his former nemesis end up in London, and that both Oliver and his current nemesis end up working for or with Fagin.

The second half also suffers from a much bigger problem: a lack of passion. In the first half, Dickens attacks, with sarcasm and verve, a range of issues he felt strongly about, or that he wanted to criticize: workhouses, orphanages, chimney cleaning safety, hypocrisy naval training, the legal system, funeral etiquette, Bow Street Runners, and people who do not check to see if trapdoors are right under their feet when they are being interrogated by very questionable, untrustworthy men hunting down dark secrets. Really, Mr. Bumble, you think so little of other people that you should have thought of this.

Ok, technically, that last bit is in the second half, and it’s hilarious, but it’s also not, strictly speaking, the sort of social issue that Dickens felt passionate enough to write about and satirize. Come to think of it, my comparison to Joss Whedon was a little off: in those first sections, Dickens is a bit more like John Oliver. That passion not only makes it clear that Dickens was talking about genuine, current problems, but gives these scenes an emotional power that even the brutal murder in the second half lacks. That first half is also rooted in a deep realism that touches on real fears of hunger and starvation and theft and injustice, where even some of the rats are starving; the second half has people not noticing trapdoors and chasing down secret wills and finding long lost aunts.

And it’s also not nearly as amusing. A word that might seem odd to use for a story basically about the many ways 19th century orphans could be exploited and abused, but which does apply to Dickens’ acerbic comments about the characters Oliver encounters. His observations about the behavior of mourners at funerals, for instance, are both horrifying and laugh out loud funny, as is his dissection of the logic used by upstanding and only slightly less upstanding moral citizens supposedly focused on Oliver’s welfare. That first half has an unintentionally amusing moment when a character predicts that cameras will never be popular because they are “too honest.” In a book like Oliver Twist, that deliberately explores the dishonesty of the human race, it’s an understandable error.

But it’s the second half that made me see the connections between Oliver Twist and the other works Disney used as source material. Oh, certainly, Oliver Twist has no overt magic, and apart from occasional digressions into the possible thoughts of a dog, no talking animals, either. But for all its early realism and concern for social issues, in many other ways it is pure fairy tale in the very best of the French salon fairy tale tradition—a tradition that was also concerned with several social issues—with its central character the innocent little orphan boy who undergoes a series of trials before getting his reward.

In this regard, it perhaps makes sense that Oliver, much like those fairy tale characters, is essentially a static character, always pure-hearted, always good. Several other characters do change throughout the course of the narrative—most notably Nancy the prostitute and Charley Bates the pickpocket—but Oliver does not. His circumstances change, but nothing else. Granted, I find it rather difficult to believe that young Oliver remains so sweet and kind and honest given the life that he’s lived, none of which really sounds like the sort of environment that encourages high moral standards—but that, too, is out of fairy tale, where the protagonist’s central personality remains the same, no matter what the circumstances.

This fairy tale structure, however, also causes one of the problems with the book’s second half: as it begins, Oliver has already received his fairy tale reward—a happy home with the Maylie family. Really, in more than one way, the story should have ended there. But popular demand wouldn’t let the story end there—and so instead, Oliver Twist becomes the less interesting saga of Oliver trying to keep that reward from various mean people that want to take it away.

Even lesser Dickens can still be a compelling read, however, and compelling Oliver Twist certainly is, even in that second half. Reading it makes it easy to see why so many films and mini series have looked to Oliver Twist for inspiration. Including a little Disney movie about a kitten.

Mari Ness lives in central Florida.